Insight Blog

Agility’s perspectives on transforming the employee's experience throughout remote transformation using connected enterprise tools.

8 minutes reading time

(1575 words)

Idiosyncratic Rater Effect & 3 Biases That Hijack Performance Reviews

We drive into the Idiosyncratic Rater Effect, Here we quantify idiosyncratic choice biases in a perceptual discrimination task and performance.

The majority of individuals don't find the process of rating, evaluating, and assessing others pleasant. Negative overtones, such as scorn, judgment, and a lack of impartiality, often arise.

As part of our previous work, we explain why traditional performance evaluations don't always yield the expected effects; precisely, they focus on only one type of feedback, evaluation. If you don't include coaching and gratitude in your evaluation feedback, you're doomed from the start.

When the feedback process is done "correctly," there may still be a sense of skepticism in the process.

There's still a problem with rater bias, even if you've created the finest HR performance management system in the world.

To have a successful assessment system, it is essential to maintain objectivity, although this is not always possible. People's perceptions might be influenced in a variety of ways when they generate performance data.

Idiosyncratic Rater Effects

Conscious or unintentional biases might affect how a person evaluates a product. They are idiosyncratic traits that impact how managers rank their employees without regard to their actual performance. Listed here are a few of the most common:

- We know that "no one is flawless," so we're getting ratings that are more in the center.

- Overemphasizing a particular ability that we regard as a mark of our own worthiness

- Evaluation based on potential rather than actual performance

- Overemphasis on the most recent events

- Value those who serve as a constant reminder of our own flaws

Ideally, an employee's performance should be the sole factor in determining a rating. Performance evaluations can be inaccurate, biased, or even unfairly treated if a person's unconscious prejudice is incorporated.

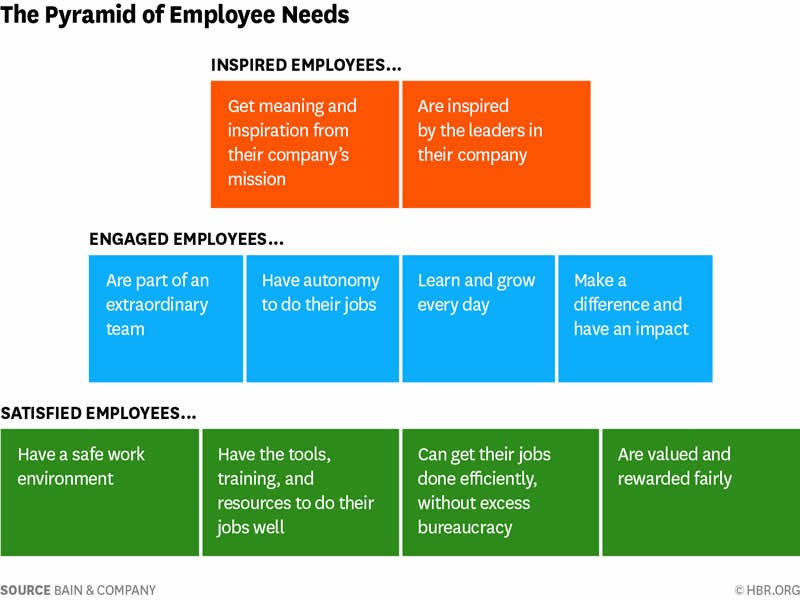

Employees who believe their performance assessments are tainted by rater bias report lower levels of work satisfaction, which is correlated with higher levels of desire to leave their current positions. As a result, it is possible to eliminate rater bias and make your performance evaluation system even more effective.

What is Idiosyncratic Bias?

In the case of idiosyncratic rater bias, managers tend to overvalue their own weaknesses. In contrast, they place a lesser value on others' abilities than they place on their own. This means that supervisors use their own peculiarities as a basis for evaluating performance.

More than half the diversity in evaluations may be attributed to the person providing the review, rather than the person being assessed, according to a major study on feedback. More important than actual performance, the performance metric being graded, the rater's perspective or even measurement error was the influence of rater bias.

A big difficulty with performance data is that the score provided frequently tells us more about the rater than about the individual being assessed.

3 Biases That Hijack Performance Reviews

Here are the 3 biases that are known to hijack performance reviews:

Similarity bias

Humans appear to have a natural tendency to divide others into "insiders" and "outsiders." As a significant drawback, we sometimes use superficial proxies like skin color or gender to determine which people are "one of us" and which are not.

An example of similarity bias is our preference for persons like ourselves at the expense of others.

If this tendency is present in the workplace, male bosses may unwittingly give preference to their male colleagues, or religious persons may favor those of the same faith. Although managers profess to be "blind" to some qualities, out-group members must strive harder to earn the manager's attention, lest they appear to be underperformers.

Is it possible to overcome the tendency to see everything as being the same?

Managers should be taught to discover something in common with an employee before presenting a performance assessment. Thus, all the advantages of attention and perception are conferred on the employee since the boss is primed to consider them as part of their in-group.

It is common for managers to begin a performance evaluation by recalling a recent work event in which they and their female employees were involved. When two individuals find similar ground, they feel more secure because their aims are linked. He can now focus on her ideas and successes because she is now part of his own group.

Distance bias

We tend to give greater importance to persons and events that are nearby, in terms of distance or time, than those that are further away in terms of distance or time. The value we naturally attach to anything rises in direct proportion to its proximity to us.

According to the example given above, it is far simpler to remember Marta's sales statistics from the recent week or month than the full year. Because previous figures are more difficult to recall, even if she has significantly improved over the last two quarters, her boss may favor her current performance.

What can you do to overcome the effect of distance bias?

You won't recall January's happenings as vividly as October's when looking back at the year as a whole. Even if Marta's performance has improved or deteriorated over time, your brain will prioritize the most recent months, so you'll pay attention to where she is right now.

It's important to keep a log of employee feedback in order to avoid distance bias in the future.

Expedience bias

The expediency bias causes us to focus on responses that appear apparent rather than ones that may be more valuable or important.

It is possible to give more weight to recent data by focusing on it first. It's possible that with the digital publication, writers may be judged simply on traffic statistics, rather than the quality of their work. The strength of customer connections may fuel future business in sales, yet revenue objectives may be the only thing on the minds of salespeople.

Why does expedience bias happen?

In order to prevent expediency bias, go beyond the data that is easy to obtain and prioritize less visible signals of success or failure, such as a person's capacity to push other team members to achieve their goals. If you want a more complete view of what a particular person contributes to your company, talk to others in other areas. Managers, of course, need to evaluate their likability and similarity biases to ensure that their opinions are fair in the process of doing so.

Asking employees about their own aspirations might also help managers conduct more objective appraisals. Additionally, an employee may wish to lead more meetings and work better as a member of the team. Because the data that is simplest to obtain is also the most relevant and complete, this method avoids the problem of expedience bias.

Idiosyncratic Rater Effect Example

Let's imagine a manager who is excellent at project management but has no knowledge of computer programming. Consequently, she awards higher points to individuals who excel at computer programming and lower marks to those who excel at project management or other related talents.

Why? A skilled project manager is more inclined to hold her employees to a higher level and compare them to her own abilities. On the other side, because she is unfamiliar with computer programming, she is more inclined to be liberal in her evaluation of performance. In other words, her criticism focuses more on her own abilities than on those of her staff members.

Errors and Biases in Performance Appraisal

It is extremely difficult to produce objective and accurate judgments free of bias, prejudice, and other subjective and external factors since human judgment is so frequently exposed to these influences.

- Halo Bias: The Halo Bias is a propensity to offer positive evaluations of a product because of a single area of excellence. The Horns Bias, on the other hand, is the inclination to assign an overall negative grade based on a single or a few poor performances.

- Recency Bias: Employees who have recently performed poorly tend to overestimate how much work they have actually done in a given time period. Employees may have done admirably during the period in question but made a grave error shortly prior to their evaluation, or they may have performed poorly until a recent accomplishment right before their evaluation.

- Leniency error: Errors of leniency occur when the rater's propensity is to rate all employees either at the high or lower extremes of the scale (negative leniency).

- The way we judge an employee may not always be based on objective factors, such as our feelings.

- Error in the central tendency: When raters avoid making "extreme" assessments about employee performance, they commit the central tendency fallacy, and as a result, the ratings given to all employees fall in the middle of a scale.

- First impression bias: If an employee's performance is evaluated based just on a single rating period, the rater may be guilty of making a mistake known as a first impression error.

- While it's common for new employees to start out strong, they may lose some of their initial vigors after a few weeks or months of work.

- Similarity bias: In performance evaluation, the propensity of the rater to favor employees who are similar to the raters themselves is known as "similarity."

Even while we may all relate to those who are similar to us, we must not allow our capacity to relate to someone to affect our assessment of their effectiveness as an employer's employee.

Categories

Blog

(2698)

Business Management

(331)

Employee Engagement

(213)

Digital Transformation

(182)

Growth

(122)

Intranets

(120)

Remote Work

(61)

Sales

(48)

Collaboration

(41)

Culture

(29)

Project management

(29)

Customer Experience

(26)

Knowledge Management

(21)

Leadership

(20)

Comparisons

(8)

News

(1)

Ready to learn more? 👍

One platform to optimize, manage and track all of your teams. Your new digital workplace is a click away. 🚀

Free for 14 days, no credit card required.